The Appeal:

The Appeal speaks to us from under the shadow of a slave society, but it is no slave narrative. It is the liberation manifesto of a free man amidst a world enchained.

David Walker attacked avarice itself, finding this urge at the root of all predatory ideology, undergirding all systems of slavery, serfdom, and oppression: “…[T]hose who are actuated by sordid avarice only, overlook the evils, which will as sure as the Lord lives, follow after the good. In fact, they are so happy to keep in ignorance and degradation, and to receive the homage and the labour of the slaves, they forget that God rules in the armies of heaven and among the inhabitants of the earth… [and] will at one day appear fully in behalf of the oppressed”[1].

David Walker’s Appeal calls for an end to slavery, but it also calls us to a much greater self-mastery and self-development. Of education, Walker offers that “I would crawl on my hands and knees through muck and mire, to the feet of a learned man, where I would sit and humbly supplicate him to instill into me, that which neither devils nor tyrants could remove” because “for coloured people to acquire learning in this country, make[s] tyrants quake and tremble on their sandy foundation.”

“[Walker’s] explicit display,” Elizabeth McHenry explains in Forgotten Readers: Recovering the Lost History of African American Literary Societies, “of the ability of a black man to read widely, reason lucidly, and write authoritatively defied claims of black intellectual inferiority and delivered a crippling blow to the prime justification for black enslavement and oppression”[2].

[1] Walker, David. David Walker’s Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World. Third and final edition, first published in 1830. Black Classic Press. Baltimore, MD. 1993.

[1] McHenry, Elizabeth. Forgotten Readers: Recovering the Lost History pf African American Literary Societies. Duke University Press. Durham and London: 2002.

[2] McHenry, Elizabeth. Forgotten Readers: Recovering the Lost History pf African American Literary Societies. Duke University Press. Durham and London: 2002.

The Appeal speaks to us from under the shadow of a slave society, but it is no slave narrative.

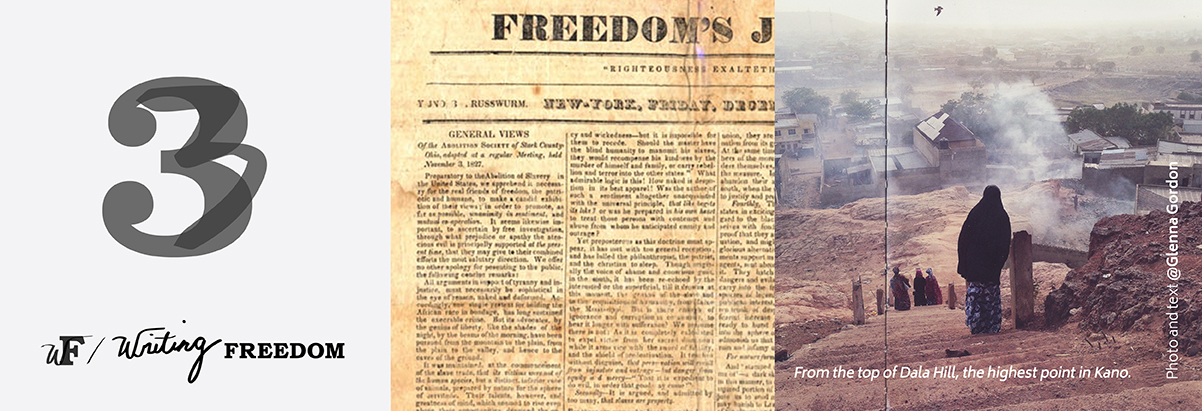

Romance Writers and Boko Haram: Opposing responses to a “volatile social climate”

Novian Whitsitt: “The romance writers, without exception, feel a sense of social responsibility in advising a youth confused by the volatile social climate” (Whitsitt, 2002).

Michelle Faul: “Boko Haram denounces the Western influences that are inextricably entwined with the romance genre — an argument author Gudaji firmly rejects. Her 16-year-old son was blinded in one eye … during a 2014 Boko Haram attack on Kano’s Grand Mosque. Gudaji says: ‘What they are preaching and doing is not in the Quran, it’s un-Islamic.’” (See Faul)

Novian Whitsitt: “Overwhelmed by the immediacy their growing pains, conservative Hausa communities often conceive of Soyayya writers as a cultural enemy. But history will view the works of these writers as vital contributions to social transformation of Hausa-Islamic culture” (Whistsitt, 2003).